Universal Design: Does Your Campus Comply?

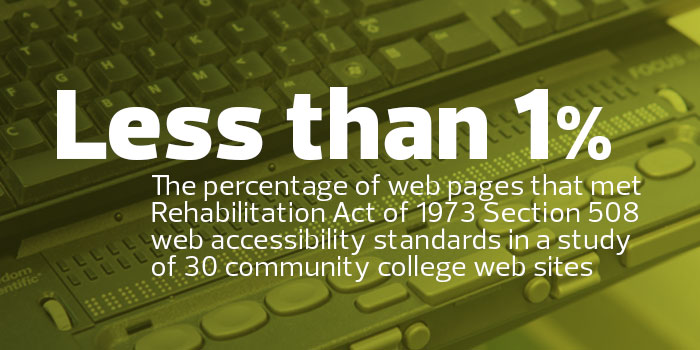

For students with disabilities — whether related to sight, cognition or dexterity — digitization in higher education curricula can create significant challenges. In some cases, students and advocacy organizations have filed complaints and lawsuits against colleges that fail to comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act and with Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, mandates requiring federally funded institutions to ensure all individuals with disabilities can use online content as effectively as other individuals.

The World Wide Web Consortium’s Web Content Accessibility Guidelines advocate for all digital content to be perceivable, operable, understandable and robust. Many institutions, including the 23-campus California State University system, are embracing these and other strategies to make accessibility a top priority.

Teach the Teachers for Better Outcomes

Kate Sharron, program manager of California State University, Northridge’s Universal Design Center, says the center strives “to educate the campus community so they incorporate accessibility considerations into their everyday work.”

The university has an Accessible Technology Initiative and a procurement process that calls for staff to evaluate products for accessibility before making a purchasing decision.

According to Rima Maldonado, a reading/alternate media services coordinator at Cal State Fresno, such efforts are essential. When students with disabilities lack user-friendly materials, they may fall behind in course work, feel isolated from class discussions and struggle to succeed in their programs.

“Accessibility is about ensuring parity of ease and experience,” says Tim Springer, CEO of consulting firm SSB Bart Group. In higher education, he says, one major challenge is accessibility of electronic documents: “A huge slice of content is created by users who have little knowledge of accessibility. This creates a significant and widespread accessibility issue.”

Kate Sharron and Patrice Wheeler of Cal State Northridge work to provide accessibility to all students.

Tech Steps In to Assist

Some institutions overcome this obstacle with native software features, such as those within Microsoft Office and the Adobe product line.

“Adobe Acrobat Pro is a very important tool our office uses to remediate PDFs,” says Patrice Wheeler, an assistive technology specialist at Cal State Northridge.

Acrobat’s built-in accessibility checker provides feedback if a PDF lacks usability features and suggests fixes. Accessible documents should include text that can be read aloud by assistive technology, images accompanied by a description (or “alternative text”) and logical organization. In Microsoft Word, users can deploy style guides to create headings, which Wheeler says are vital for helping visually or cognitively impaired students effectively navigate a document.

“People who are blind or have low vision don’t use visual cues to read, skim or navigate text,” she says. “They need a roadmap of sorts, and headings and styles provide that to them via their assistive technology.”

Wheeler says Cal State Northridge teaches faculty and staff to craft accessible text, properly tag images and caption videos, and include ease-of-use structures in every document, from syllabi to study materials.

In 2015, Michigan State University’s Usability/Accessibility Research and Consulting team hosted the Making Learning Accessible Conference. One of their key takeaways: In training students, faculty and staff to design universally accessible courses, content and websites, small changes — such as taking a few minutes to format a Word document or include alternative text — can make a huge difference for users.

Creating a New Toolkit

Many campuses rely on software and other tools specifically developed for students with disabilities. Cal State Northridge provides Dragon NaturallySpeaking, which turns spoken words into text and executes voice commands, allowing students to dictate and edit documents and spreadsheets, send email, search the web and use social media.

The university also uses the JAWS (Job Access With Speech) screen reader, which provides speech and Braille output for popular applications, as well as Read & Write Gold literacy software, which helps students (especially those with dyslexia) read independently, understand unfamiliar words and hear/check their spelling. Another important tools is CryptZone’s Compliance Sheriff, which scans content, identifies areas of risk and detects policy violations to address a wide range of web compliance issues, including accessibility.

Erik J. Escareño, who graduated from Cal State Northridge in 2015 with a double major in linguistics and deaf studies, is enrolled in CSUN’s master’s of social work program. He uses scanners and software applications to convert printed textbooks and digital materials into a format that’s readable by text-to-speech. For writing, he uses Dragon NaturallySpeaking.

“Keeping up with my books can be challenging,” Escareño says, “but using the technology provided by Disability Resources and Educational Services has made reading my textbooks easier.”

Other campuses use tools such as Braille embossers and refreshable Braille displays; screen enlargers and magnifiers; alternative keyboards, which let users select keys with a mouse, touch screen, trackball, joystick, switch or electronic pointing device; screen readers that verbalize text, graphics, control buttons and menus into a computerized voice; and voice recognition programs that allow students to issue commands and enter data through voice commands.

SOURCE: Community College Journal of Research and Practice, "The Accessibility and Usability of College Websites."

Accessibility for Every User on Every Device

Although the desktop computer remains the primary tool for many people with disabilities, mobile accessibility is becoming more important, Springer says. “Learning is going with you wherever you go; accessibility needs to follow that experience. All those channels need to be accessible and usable.”

Sharron at Cal State Northridge agrees, pointing to new features, such as speech-based screen readers, that make mobile platforms easier to use.

Alongside the new capabilities afforded by technology solutions, Wheeler emphasizes that educators and technologists should remember the human aspect, as each individual brings his or her own expertise and experience to the table. She also recommends that institutions stay agile and adaptable, because technology is a moving target.

“Accessibility is a journey, not a destination,” she says. “There’s always going to be more to know and do.”